Woollett told Redman that he was outside the Honda enclosure at the time the photos were taken, so Redman had no right to record the valuable film.

Of course, Woollett wouldn't have known he really had the chance until he returned to the UK on Monday morning to have his films developed and submit his report for MCN, which was (and still is) published every Wednesday.

Things were completely different back then. Woollett thought nothing of driving a Triumph Trophy sidecar (loaded with typewriter, cameras, leather racing suits and everything else) all the way to Salzburg for the Austrian Grand Prix (how many stops for road maintenance?!), taking photos, Writing reports, taking part in the sidecar GP (he has been a co-driver for various drivers over the years) and then driving home with the trophy on Sunday evening. And that was before the days of roll-on-roll-off Channel ferries.

Anyway, back to the photo of the GP24 and what's so interesting about it?

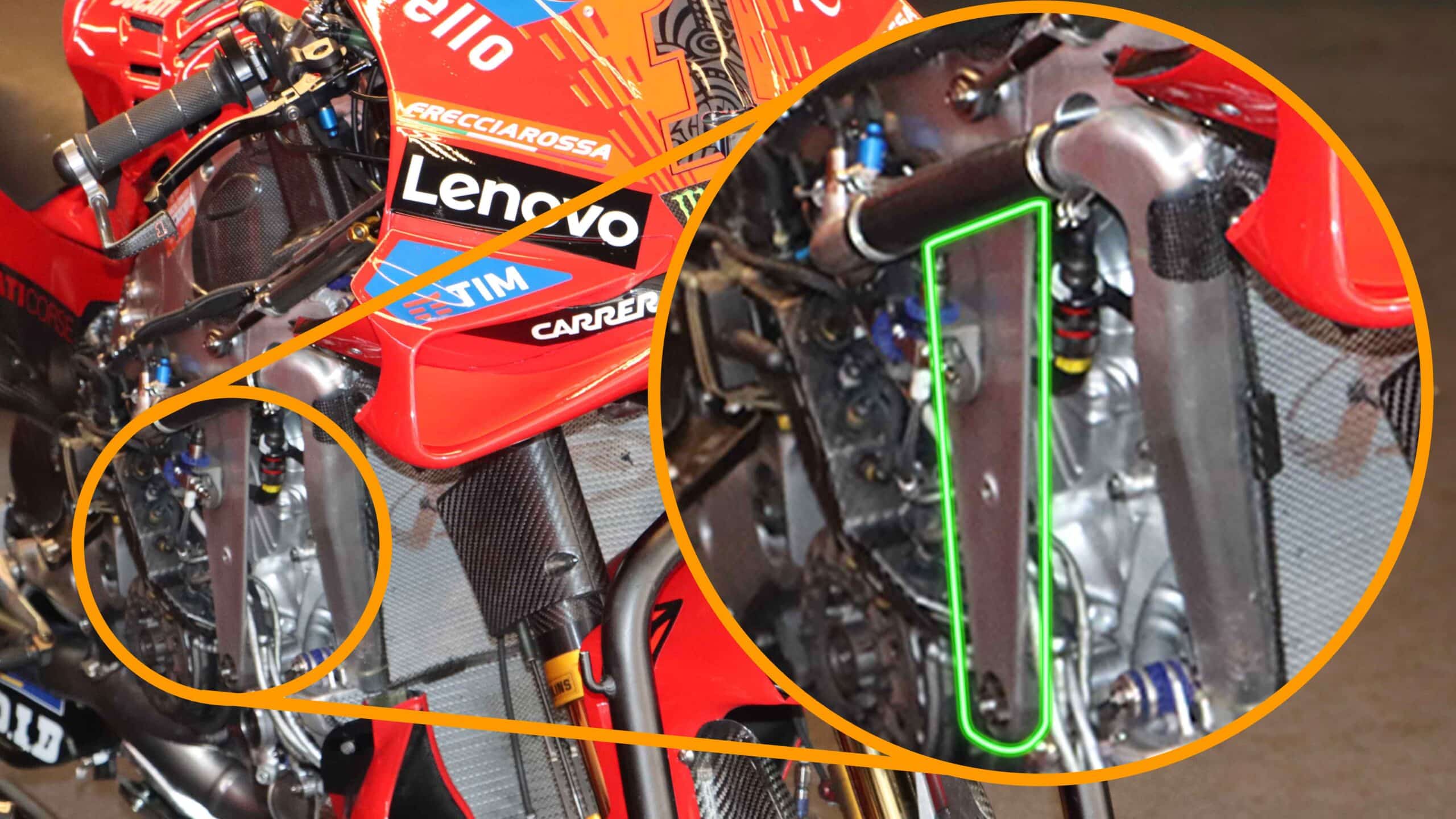

Look at the front engine mount (the aluminum alloy vertical arm partially hidden by a radiator hose). It's super long and super thin – much, much thinner than any engine mount I've seen on a MotoGP bike.

It's so thin – just a few millimeters thick – that it looks more like a cheap shelf bracket you can buy at a hardware store. And it almost looks like it was stamped and not CNC-milled from solid as usual.

It carries the steering damper on its top and is welded to the steering head part of the frame. Below it is bolted to the lower front engine mounts of the V4 engine (hence engine mount).

Why is it so thin? Because front engine mounts are an excellent way to create the lateral flex required for a racing motorcycle chassis.

A crashed 2022 Yamaha YZR-M1 shows the thin but very wide front engine bar. The thinness ensures lateral bending when cornering, the width ensures longitudinal rigidity when braking and accelerating

Gold and goose

When a motorcycle uses a lot of lean angle in a corner, the suspension doesn't really work because it's at such an acute angle to the road. However, the rider must pay urgent attention to ensure that the motorcycle absorbs bumps in the road and continues to follow the surface perfectly.

So the engineers build lateral flex into the chassis (lateral meaning left and right, which changes up and down when the bike is on its side!) so that at full tilt the chassis flexes up and down and stuff generates its own suspension movement.

If the bike doesn't follow the road, the tires don't grip the asphalt, and if the tires don't grip, the bike goes too far and can't go around the corner quickly and quickly, costing valuable time.

And what was Ducati's age-old problem? Turn in the middle of the curve. And that's what the rival engineer told me when I showed him the GP24's super-thin engine bar: “Lateral flex, for turning.”

Honda's great 2002 RC211V was one of the first GP bikes to use longer front engine mounts to give engineers the ability to create lateral flex

Honda

The last Desmosedici I saw partially naked was a GP15, the first designed by Gigi Dall'Igna. The front engine mount was slightly shorter, milled from solid material and more than ten millimeters thick. The latest hanger obviously allows for much more flexibility when the bike is tilted forward. It is almost certainly this feature that contributed to the Desmosedici's improved cornering ability, which has helped the bike dominate in recent years, although some bikes are still better in the middle of corners.

All manufacturers have become increasingly thinner in the search for controlled flex in various sections of their frames and swingarms. If you snap some casing parts with your fingernail, they are so thin – about 1.2mm – that they ring like a beer can, but usually this thinness is compensated for by larger overall sections.

Take a look at the Yamaha YZR-M1 and you'll see that the engine mount is very wide, because while the engineers want the bike to flex when it's on its side, they don't want it to flex while doing so Longitudinal (longitudinal, not sideways) bends The driver brakes or accelerates while upright or nearly upright as this would cause problematic instability.

Therefore, Ducati must have regained some longitudinal rigidity elsewhere to keep the bike stable. But I don't expect them to tell me where or how!

Comments are closed.